In this photograph of Spokane in 1914 you can see what is now called the Jensen-Byrd warehouse just to southwest of the tall smokestack toward the middle of the image.

Historic Preservation is much more than rehabbing old homes to look pretty again. Preserving the built environment sometimes takes an army and almost as many resources. In Beyond Preservation: Using Public History to Revitalize Inner Cities Andrew Hurley discusses different projects he has been involved with and how those projects played out. Beyond Preservation provides readers with a brief history of the preservation movement beginning with the late nineteenth century and emphasizing post-WWII. After the war “between 1947 and 1967, 383,000 dwelling units surrendered to the wrecking ball and more than 600,000 residents were displaced from their homes. African Americans constituted 80 percent of these refugees.” (10) The National Highway Act divided up cities and generally poor neighborhoods were targeted for demolition as they did not have the means to fight back to preserve their homes and neighborhoods.

By the 1960s with the passage of the Historic Preservation Act the federal government and many state and local governments gave significant tax breaks and incentives for preserving historic buildings instead of bulldozing them to build new structures. But this “entrepreneurial version of historic preservation that flourished after 1966 placed a greater emphasis on the economic potential of aging buildings and landmarks than on their ability to foster a shared sense of belonging.” (19) In short, people were in it for the money. But as communities saw these old dilapidated buildings adaptively reused many saw the potential in bringing whole neighborhoods back from the dead. After tax brakes waned in the 1980s and there was less economic incentive to big developers historic preservation became a more community oriented enterprise.

Hurley provides a variety of examples of different communities engaging in their history in order to make their future more bright. Communities have a variety of reasons why they want to highlight their history whether for tourism, economic development, local pride, or community engagement to name a few. But many in communities are wary of preservation as “in time, entire populations turned over, with affluent newcomers having in essence evicted the poorer residents, both renters and owners.” (26) With preservation typically comes increased property values pricing out lower income and racially diverse peoples, gentrifying neighborhoods that never were homogenous. In tackling a variety of projects around St. Louis including the Old North St. Louis, Lewis Place, Forest Park, and various historic sites Hurley argues for a more inclusive look at history. Public historians involved with these projects need to be sensitive to community needs, but also engage with the public, environmentalists, archaeologists, and oral histories.

There are obstacles for academic historians to get involved in community projects including academic emphasis on the keeping the bureaucracy of a university running tenure and promotion, and emphasis on publishing. “Through these outlets, scholars communicate primarily with their peers. Heavily referenced and couched in abstruse theoretical frameworks, much of this work remains inaccessible to lay audiences and thus does little to help urban communities expand their self-knowledge.” (150) Hurley points out universities are warming slowly to having their faculty engaged with the community as many have seen the benefits of university engagement with the surrounding population.

One example of historic preservation in Spokane, Washington provides a few examples of the complexity of historic preservation. in 2001, Washington State University acquired property in the downtown area to create what is now known as the Riverpoint Campus of WSU and EWU. On this property was an old warehouse known by is large ghost sign, Jenson-Byrd. This brick warehouse was built in the early twentieth century, but WSU deemed this property unnecessary and preferred to “demolish the old building and replace it with a five-story student apartment complex with 425 beds in two- and four-bedroom units with shared bathrooms and shared common areas.” (SR Dec. 14, 2011) Luckily a group of citizens thought this was irresponsible to tear down a huge historic building for student apartments when it could be adaptively reused or altered for a similar price. To make a long story short WSU did end up engaging with a community they initially upset and decided to keep the building and are currently in the planning phase of the remodel.

Preservation is hard and complicated. Even people with the same goal have differing opinions on how to accomplish that goal. But as Hurley points out “democratizing the interpretation of urban landscapes in the pursuit of consensus requires patience, diplomacy, and willingness among all participants to compromise.” (174) With these words in mind it can, and should, be done.

Would Hodge think these guys were just a bunch of Farbs?

Would Hodge think these guys were just a bunch of Farbs?

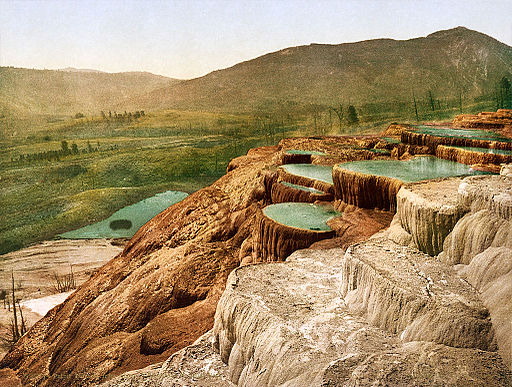

After much debate, negotiation, and contention the site is open to the public.

After much debate, negotiation, and contention the site is open to the public.